In 1887, the English government passed a law requiring products manufactured outside of England to be labeled with their country of origin to protect British products from foreign copycats of lower quality. Still today, the label “Made in…” likely has one of the most significant impacts on people’s perceptions, value attribution and purchasing behavior across product categories, both positively and negatively.

As more manufacturing, has moved to developing countries, even brands that are among the strongest in the world – such as Apple – fear the (negative) impact of the country of origin effect and print “Designed by Apple in California”, before adding the “Assembled in China” label.

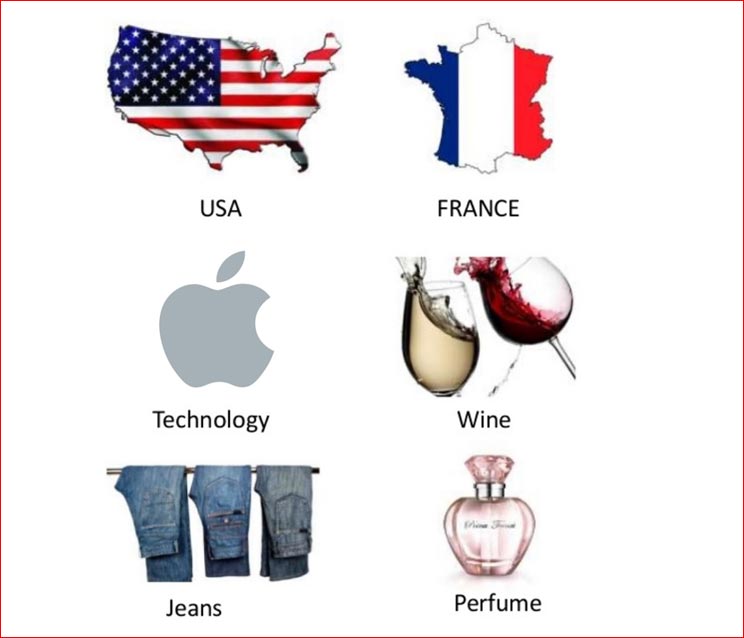

Certain countries stand for excellence in specific product categories, such as the U.S. for technology or France for wine, influencing strongly consumers’ perception of a company’s products and services depending on where it comes from.

Thus, while companies from certain countries might benefit from a positive country reputation, startups from emerging economies or transition markets that have not yet built up a strong track record in any product category, should deal with a negative country-of origin (COO) effect, or at least, compete with leading economies with a positive COO effect. In addition, dealing with liabilities of newness and the challenges that internationalization brings by itself can make this situation extremely difficult.

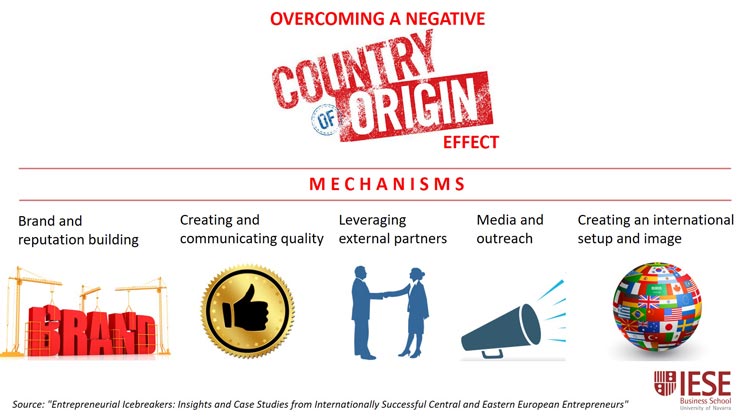

What can these startups do to survive? Based on our research on startups from post-Soviet economies in Central and Eastern Europe and Russia the 1990’s, these are the mechanisms that they can use:

As can be seen above, there are multiple ways to tackle the COO effect. Based on our research, for the transition entrepreneurs the credibility building is most effective through leveraging stakeholders. Real cases prove that it is the fastest way to succeed in international markets, however, potential disadvantages need to be considered, evaluated and mitigated as far as it is possible. Obviously, each case is different and there are no standard answers to different realities, so entrepreneurs need to experiment with the mechanisms and see their impact as they forge ahead.

In our next post, we display Growth strategies and internationalization

Prats, Mª Julia; Sosna, Marc; Sysko-Romanczuk, Sylwia, “Entrepreneurial Icebreakers: Insights and Case Studies from Internationally Successful Central and Eastern European Entrepreneurs”, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Buy the book here.

No related posts.

Mª Julia Prats is Professor and head of department of Entrepreneurship, and holder of the Bertrán Foundation Chair of Entrepreneurship at IESE. She holds a DBA in business administration from Harvard University, an MBA from IESE Business School, and a degree in industrial engineering from the Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya.

Pau is a Research Assistant at the Entrepreneurship Department where he focuses on projects related to entrepreneurship, professional service companies and profitable growth. He studied International Business at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra and has previously worked at Apple and Mango in the areas of sales and product management.

IESE Learning Innovation Unit , Associate Director