Over the past 50 years – from the Silent Generation’s young adulthood to that of Millennials today – the United States has undergone large cultural and societal shifts. Now that the youngest Millennials are adults, how do they compare with those who were their age in the generations that came before them?

In general, they’re better educated – a factor tied to employment and financial well-being – but there is a sharp divide between the economic fortunes of those who have a college education and those who don’t.

Millennials have brought more racial and ethnic diversity to American society. And Millennial women, like Generation X women, are more likely to participate in the nation’s workforce than prior generations.

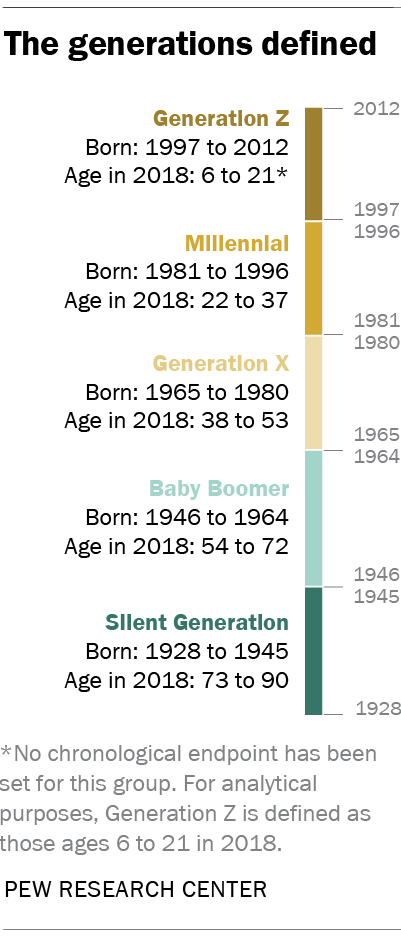

Compared with previous generations, Millennials – those ages 22 to 37 in 2018 – are delaying or foregoing marriage and have been somewhat slower in forming their own households. They are also more likely to be living at home with their parents, and for longer stretches.

And Millennials are now the second-largest generation in the U.S. electorate (after Baby Boomers), a fact that continues to shape the country’s politics given their Democratic leanings when compared with older generations.

Those are some of the broad strokes that have emerged from Pew Research Center’s work on Millennials over the past few years. Now that the youngest Millennials are in their 20s, we have done a comprehensive update of our prior demographic work on generations. Here are the details.

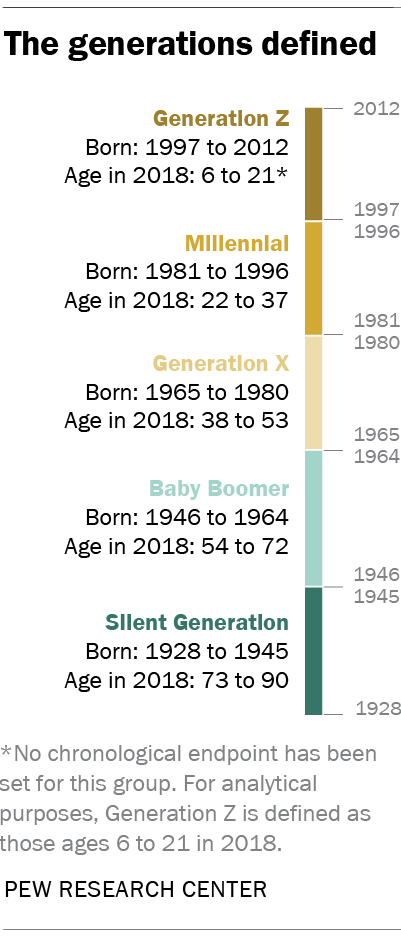

Today’s young adults are much better educated than their grandparents, as the share of young adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher has steadily climbed since 1968. Among Millennials, around four-in-ten (39%) of those ages 25 to 37 have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with just 15% of the Silent Generation, roughly a quarter of Baby Boomers and about three-in-ten Gen Xers (29%) when they were the same age.

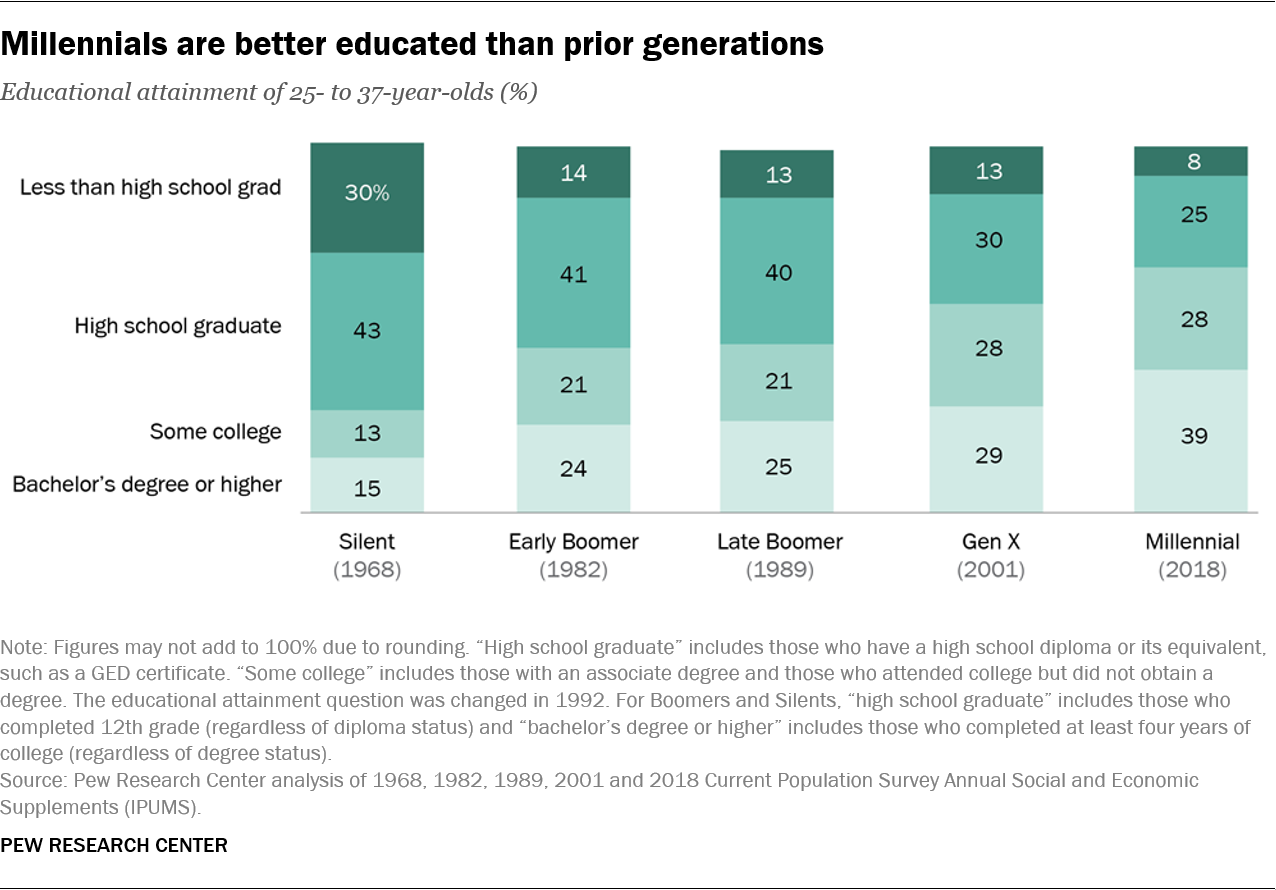

Gains in educational attainment have been especially steep for young women. Among women of the Silent Generation, only 11% had obtained at least a bachelor’s degree when they were young (ages 25 to 37 in 1968). Millennial women are about four times (43%) as likely as their Silent predecessors to have completed as much education at the same age. Millennial men are also better educated than their predecessors. About one-third of Millennial men (36%) have at least a bachelor’s degree, nearly double the share of Silent Generation men (19%) when they were ages 25 to 37.

While educational attainment has steadily increased for men and women over the past five decades, the share of Millennial women with a bachelor’s degree is now higher than that of men – a reversal from the Silent Generation and Boomers. Gen X women were the first to outpace men in terms of education, with a 3-percentage-point advantage over Gen X men in 2001. Before that, late Boomer men in 1989 had a 2-point advantage over Boomer women.

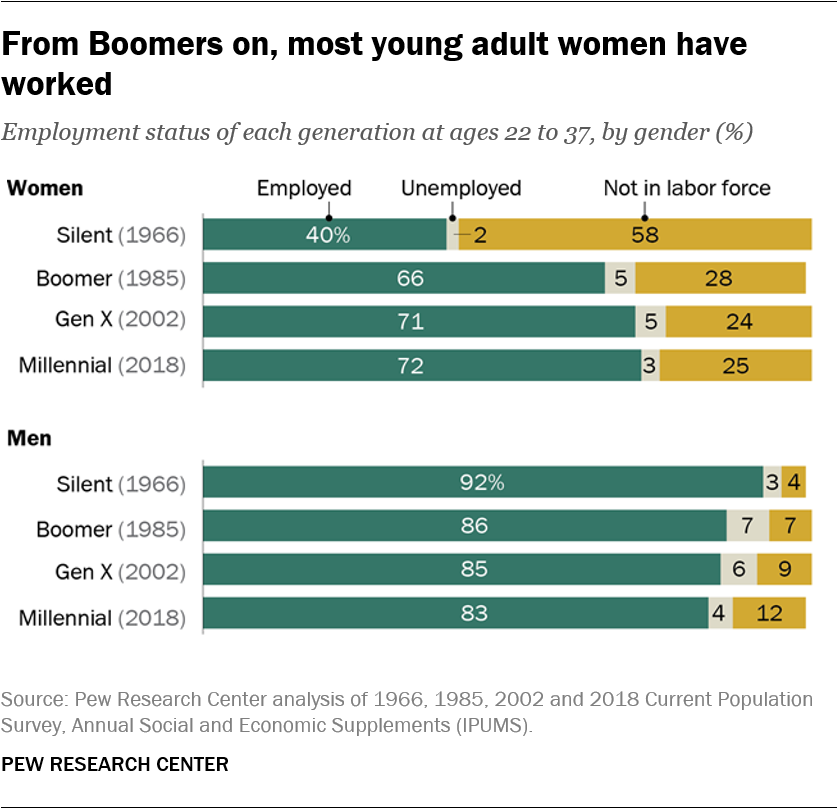

Boomer women surged into the workforce as young adults, setting the stage for more Gen X and Millennial women to follow suit. In 1966, when Silent Generation women were ages 22 through 37, a majority (58%) were not participating in the labor force while 40% were employed. For Millennial women today, 72% are employed while just a quarter are not in the labor force. Boomer women were the turning point. As early as 1985, more young Boomer women were employed (66%) than were not in the labor force (28%).

And despite a reputation for job hopping, Millennial workers are just as likely to stick with their employers as Gen X workers were when they were the same age. Roughly seven-in-ten each of Millennials ages 22 to 37 in 2018 (70%) and Gen Xers the same age in 2002 (69%) reported working for their current employer at least 13 months. About three-in-ten of both groups said they’d been with their employer for at least five years.

Of course, the economy varied for each generation. While the Great Recession affected Americans broadly, it created a particularly challenging job market for Millennials entering the workforce. The unemployment rate was especially high for America’s youngest adults in the years just after the recession, a reality that would impact Millennials’ future earnings and wealth.

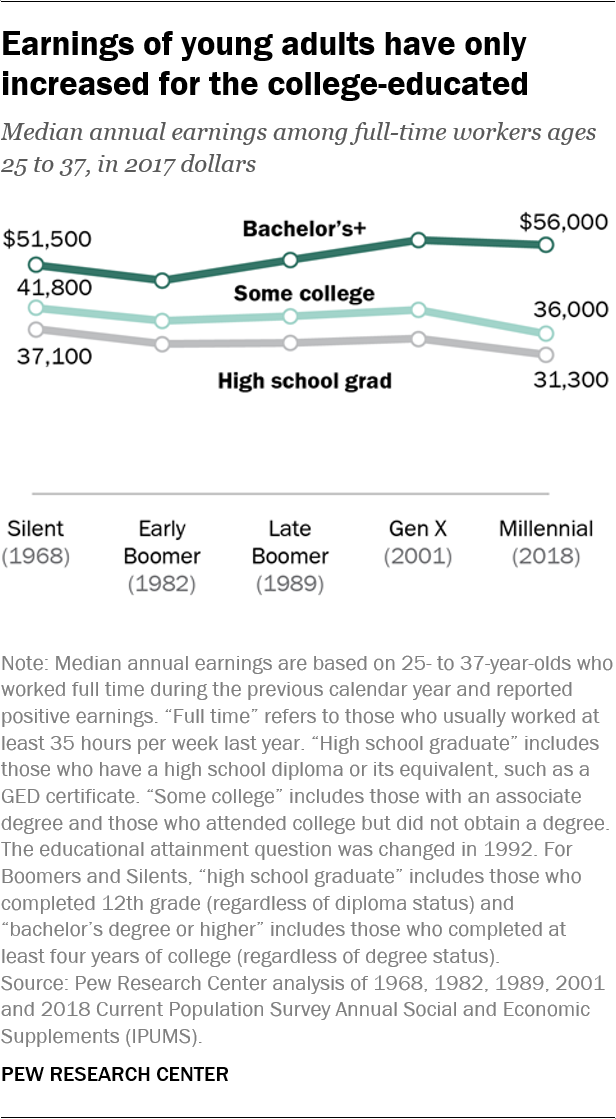

The financial well-being of Millennials is complicated. The individual earnings for young workers have remained mostly flat over the past 50 years. But this belies a notably large gap in earnings between Millennials who have a college education and those who don’t. Similarly, the household income trends for young adults markedly diverge by education. As far as household wealth, Millennials appear to have accumulated slightly less than older generations had at the same age.

Millennials with a bachelor’s degree or more and a full-time job had median annual earnings valued at $56,000 in 2018, roughly equal to those of college-educated Generation X workers in 2001. But for Millennials with some college or less, annual earnings were lower than their counterparts in prior generations. For example, Millennial workers with some college education reported making $36,000, lower than the $38,900 early Baby Boomer workers made at the same age in 1982. The pattern is similar for those young adults who never attended college.

Millennials in 2018 had a median household income of roughly $71,400, similar to that of Gen X young adults ($70,700) in 2001. (This analysis is in 2017 dollars and is adjusted for household size. Additionally, household income includes the earnings of the young adult, as well as the income of anyone else living in the household.)

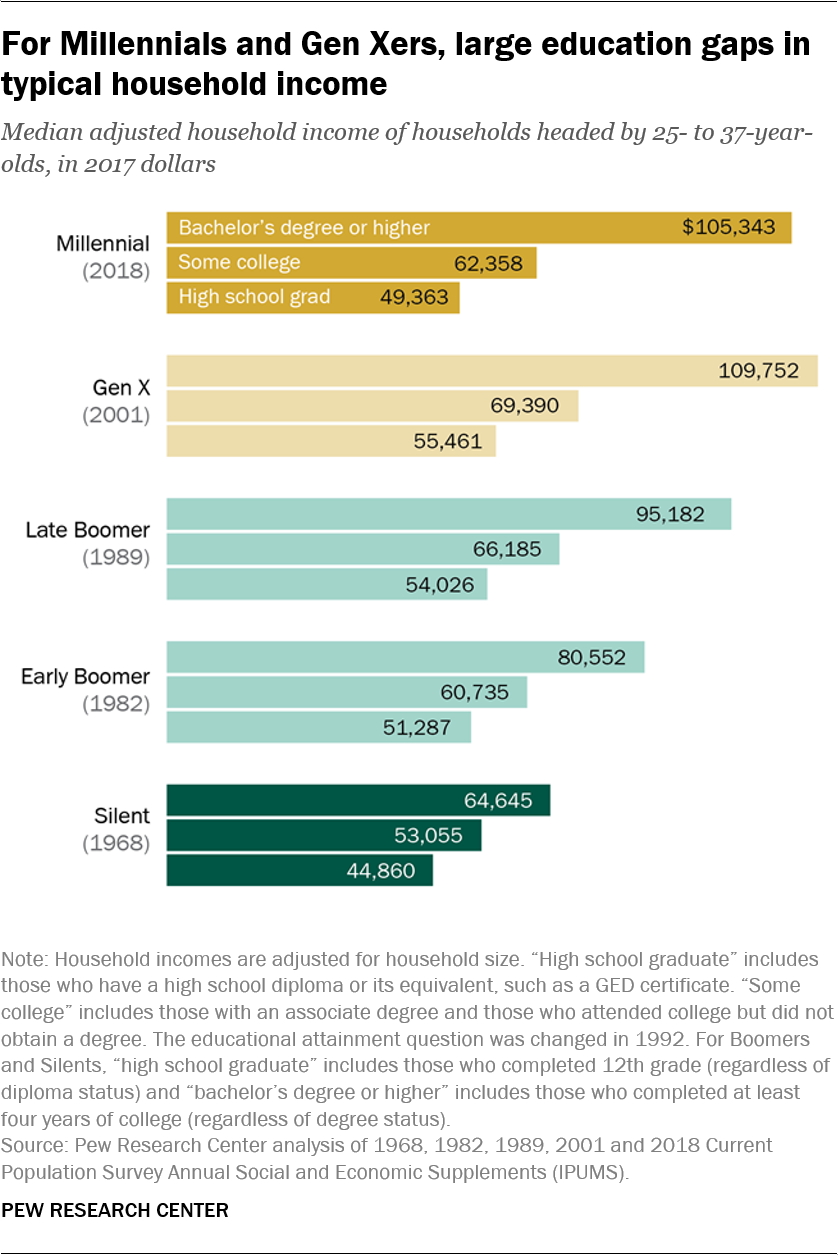

The growing gap by education is even more apparent when looking at annual household income. For households headed by Millennials ages 25 to 37 in 2018, the median adjusted household income was about $105,300 for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, roughly $56,000 greater than that of households headed by high school graduates. The median household income difference by education for prior generations ranged from $41,200 for late Boomers to $19,700 for the Silent Generation when they were young.

While young adults in general do not have much accumulated wealth, Millennials have slightly less wealth than Boomers did at the same age. The median net worth of households headed by Millennials (ages 20 to 35 in 2016) was about $12,500 in 2016, compared with $20,700 for households headed by Boomers the same age in 1983. Median net worth of Gen X households at the same age was about $15,100.

This modest difference in wealth can be partly attributed to differences in debt by generation. Compared with earlier generations, more Millennials have outstanding student debt, and the amount of it they owe tends to be greater. The share of young adult households with any student debt doubled from 1998 (when Gen Xers were ages 20 to 35) to 2016 (when Millennials were that age). In addition, the median amount of debt was nearly 50% greater for Millennials with outstanding student debt ($19,000) than for Gen X debt holders when they were young ($12,800).

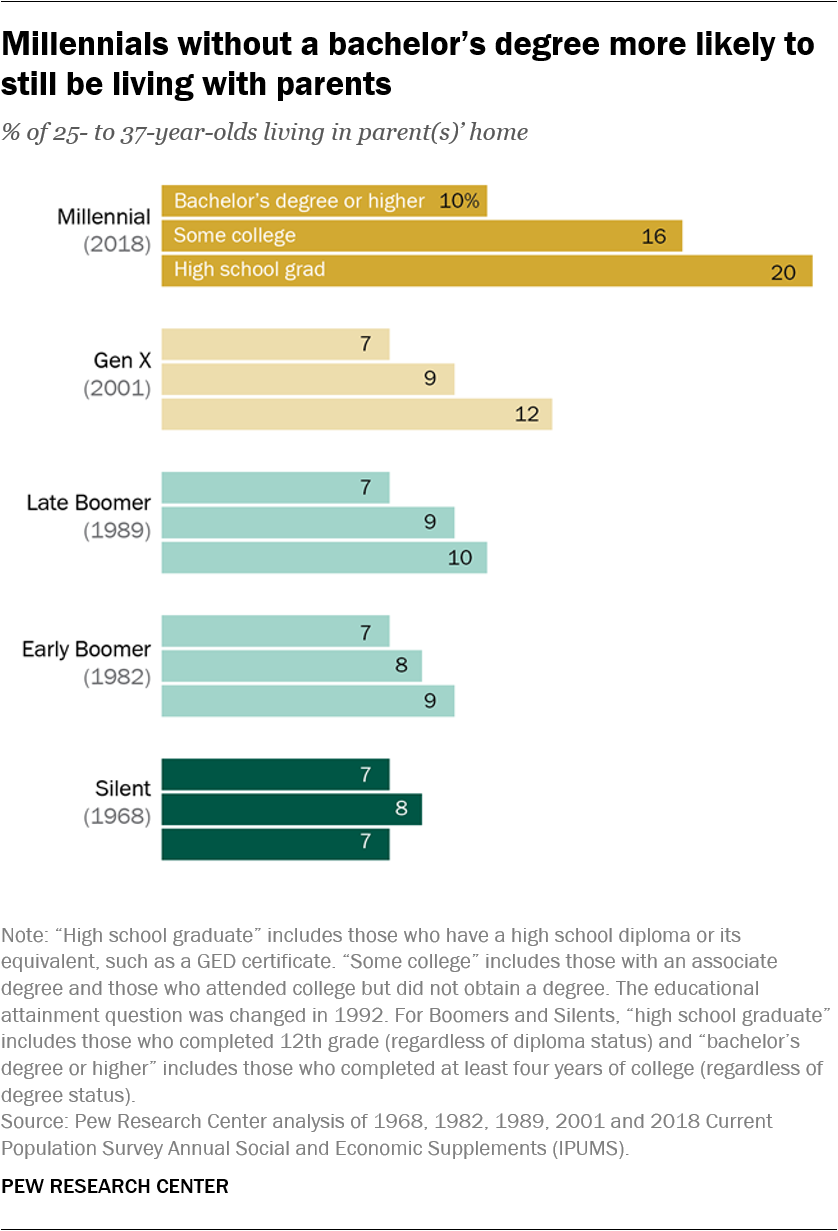

Millennials, hit hard by the Great Recession, have been somewhat slower in forming their own households than previous generations. They’re more likely to live in their parents’ home and also more likely to be at home for longer stretches. In 2018, 15% of Millennials (ages 25 to 37) were living in their parents’ home. This is nearly double the share of early Boomers and Silents (8% each) and 6 percentage points higher than Gen Xers who did so when they were the same age.

The rise in young adults living at home is especially prominent among those with lower education. Millennials who never attended college were twice as likely as those with a bachelor’s degree or more to live with their parents (20% vs. 10%). This gap was narrower or nonexistent in previous generations. Roughly equal shares of Silents (about 7% each) lived in their parents’ home when they were ages 25 to 37, regardless of educational attainment.

Millennials are also moving significantly less than earlier generations of young adults. About one-in-six Millennials ages 25 to 37 (16%) have moved in the past year. For previous generations at the same age, roughly a quarter had.

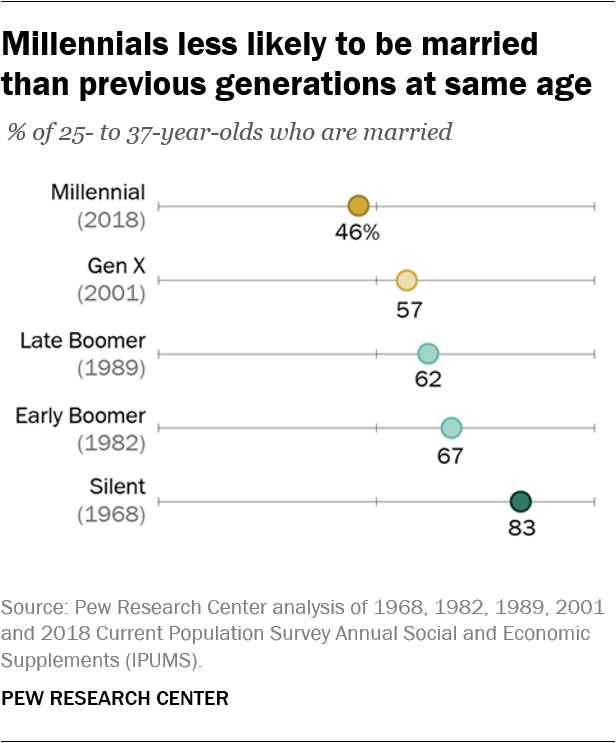

On the whole, Millennials are starting families later than their counterparts in prior generations. Just under half (46%) of Millennials ages 25 to 37 are married, a steep drop from the 83% of Silents who were married in 1968. The share of 25- to 37-year-olds who were married steadily dropped for each succeeding generation, from 67% of early Boomers to 57% of Gen Xers. This in part reflects broader societal shifts toward marrying later in life. In 1968, the typical American woman first married at age 21 and the typical American man first wed at 23. Today, those figures have climbed to 28 for women and 30 for men.

But it’s not all about delayed marriage. The share of adults who have never married is increasing with each successive generation. If current patterns continue, an estimated one-in-four of today’s young adults will have never married by the time they reach their mid-40s to early 50s – a record high share.

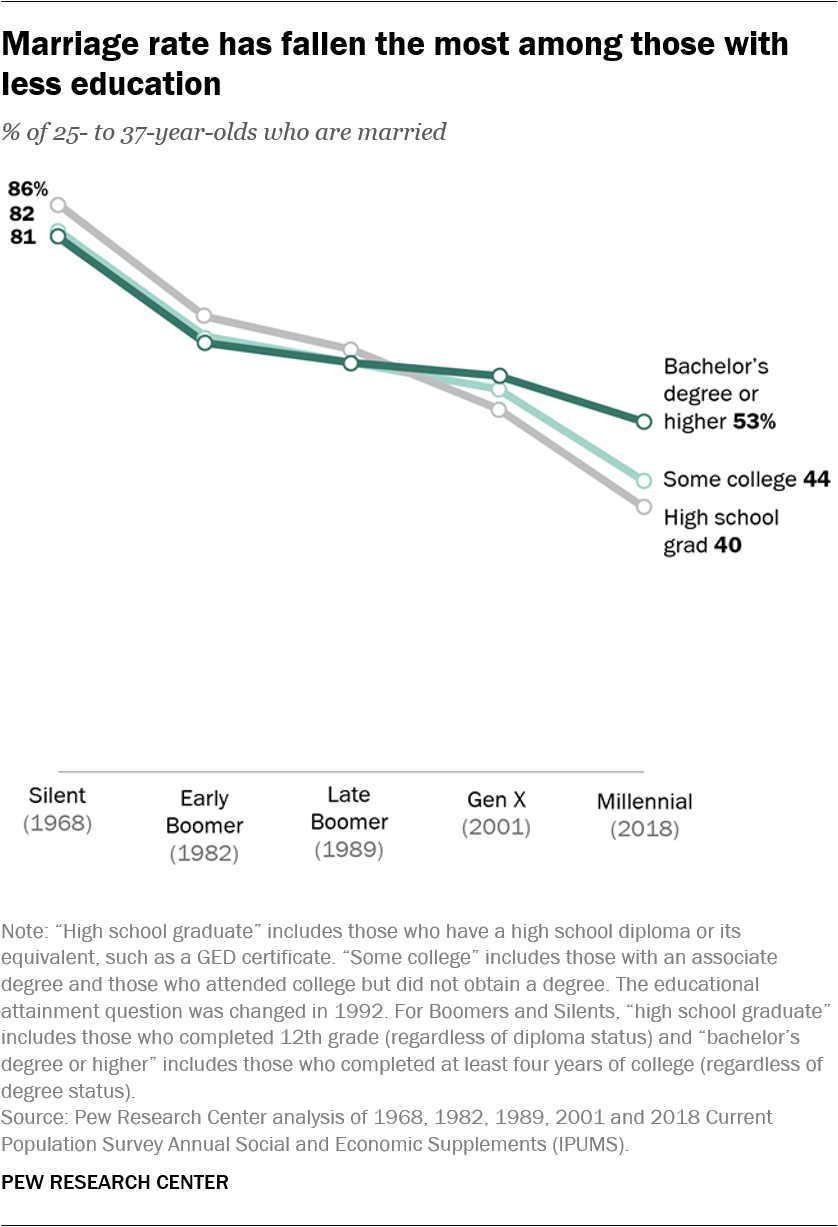

In prior generations, those ages 25 to 37 whose highest level of education was a high school diploma were more likely than those with a bachelor’s degree or higher to be married. Gen Xers reversed this trend, and the divide widened among Millennials. Four-in-ten Millennials with just a high school diploma (40%) are currently married, compared with 53% of Millennials with at least a bachelor’s degree. In comparison, 86% of Silent Generation high school graduates were married in 1968 versus 81% of Silents with a bachelor’s degree or more.

Millennial women are also waiting longer to become parents than prior generations did. In 2016, 48% of Millennial women (ages 20 to 35 at the time) were moms. When Generation X women were the same age in 2000, 57% were already mothers, similar to the share of Boomer women (58%) in 1984. Still, Millennial women now account for the vast majority of annual U.S. births, and more than 17 million Millennial women have become mothers.

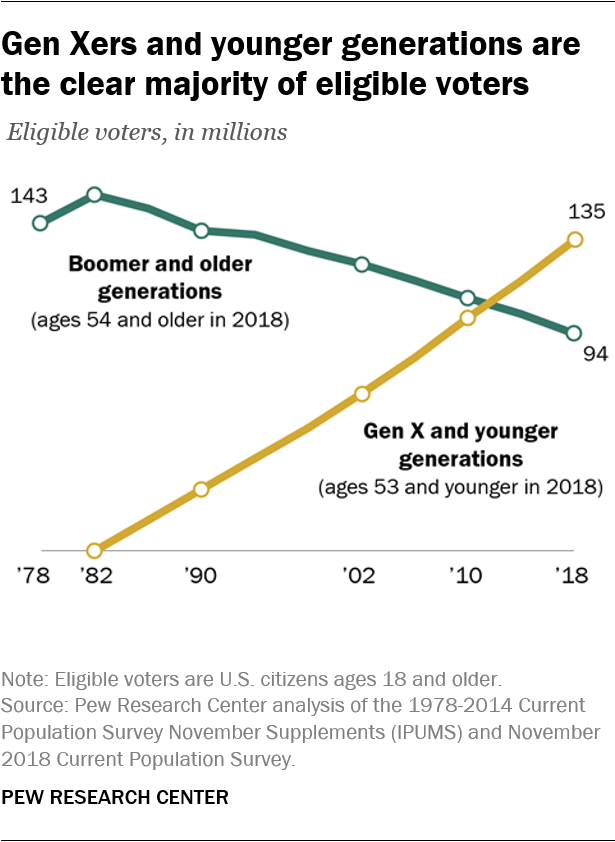

Younger generations (Generation X, Millennials and Generation Z) now make up a clear majority of America’s voting-eligible population. As of November 2018, nearly six-in-ten adults eligible to vote (59%) were from one of these three generations, with Boomers and older generations making up the other 41%.

However, young adults have historically been less likely to vote than their older counterparts, and these younger generations have followed that same pattern, turning out to vote at lower rates than older generations in recent elections.

In the 2016 election, Millennials and Gen Xers cast more votes than Boomers and older generations, giving the younger generations a slight majority of total votes cast. However, higher shares of Silent/Greatest generation eligible voters (70%) and Boomers (69%) reported voting in the 2016 election compared with Gen X (63%) and Millennial (51%) eligible voters. Going forward, Millennial turnout may increase as this generation grows older.

Generational differences in political attitudes and partisan affiliation are as wide as they have been in decades. Among registered voters, 59% of Millennials affiliate with the Democratic Party or lean Democratic, compared with about half of Boomers and Gen Xers (48% each) and 43% of the Silent Generation. With this divide comes generational differences on specific issue areas, from views of racial discrimination and immigration to foreign policy and the scope of government.

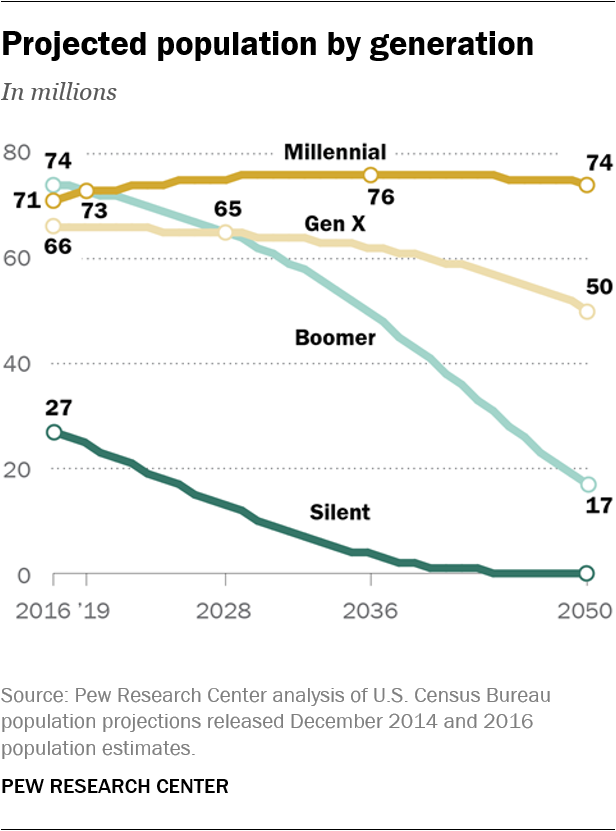

By 2019, Millennials are projected to number 73 million, overtaking Baby Boomers as the largest living adult generation. Although a greater number of births underlie the Baby Boom generation, Millennials will outnumber Boomers in part because immigration has been boosting their numbers.

Millennials are also bringing more racial and ethnic diversity. When the Silent Generation was young (ages 22 to 37), 84% were non-Hispanic white. For Millennials, the share is just 55%. This change is driven partly by the growing number of Hispanic and Asian immigrants, whose ranks have increased since the Boomer generation. The increased prevalence of interracial marriage and differences in fertility patterns have also contributed to the country’s shifting racial and ethnic makeup.

Looking ahead at the next generation, early benchmarks show Generation Z (those ages 6 to 21 in 2018) is on track to be the nation’s most diverse and best-educated generation yet. Nearly half (48%) are racial or ethnic minorities. And while most are still in K-12 schools, the oldest Gen Zers are enrolling in college at a higher rate than even Millennials were at their age. Early indications are that their opinions on issues are similar to those of Millennials.

Of course, Gen Z is still very young and may be shaped by future unknown events. But Pew Research Center looks forward to spending the next few years studying life for this new generation as it enters adulthood.

All photos via Getty Images